MOTHERLAND

Chelsea Dwarika

I’m from Trinidad,

in the Caribbean, born, raised,

and left.

When did I last visit?

I actually haven’t been back, it’s complicated. My childhood home was lost to a landslide and the world, as it does, went on without me.

But my mother, Camille, was my first home ——

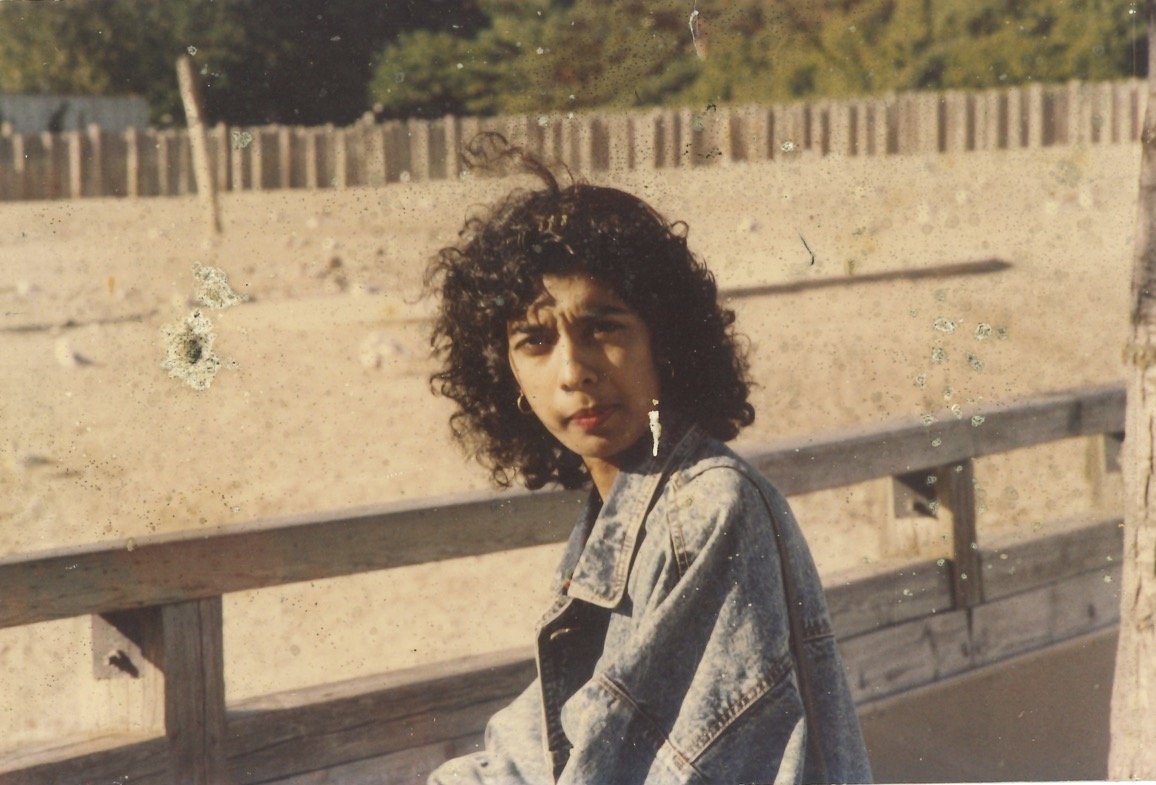

——— She is: poetry, daily DuoLingo French lessons, dark curls, red lipstick, Orange Pekoe tea, filling pitchers with passionfruit and lime juice, passing me the needle so I can thread it for her in low light. She covers her mouth when she laughs and she loves spending a day off unbothered, reading in bed, watching her dramas. Up at the crack of dawn. I can close my eyes and hear her putting slippers on to walk downstairs into the kitchen. In my cruel teenage years the only communication I recall is her poorly–spaced text messages. “come eat..Will you.be late? Door is open.”

People will tell you (infuriatingly) as a woman that you’ll change your mind about not wanting kids. I’m content, really, but I’m so in awe of the mother figures in my life who’ve led with care, softness, firm guidance, unconditional love–really doing the best they could with what they had. Most of us are determined to do the opposite of whatever brand of fucked – up our parents gave to us. To do better. I think we might be destined to fail in some capacity, to become them anyway and not recognize it until much later on. Maybe we’ll get some things right, but more likely than not we’ll just be flawed in different ways.

When I called Camille for Mother’s Day this year, I asked her what she thought her life would be like if she wasn’t a mom. My mom. “Do you feel like you gave anything up?”

She dismisses it: “Yeah, sure, but I couldn’t wait to be your mom. Did you know I bought you books before you were born? We listened to classical music because I heard it was good for the baby.”

I was so surprised–I realized that the answer I expected (maybe: travel, a career, freedom?) was mine, not hers. She wanted me, even if it was hard, even if she doesn’t feel like she got it all right.

I dream often about traveling with Mom–to Paris, to Martinique, to the ocean, to all my little corners of Montreal.

I drove us to the Okanagan one August to drink wine, dip our toes in the lake and eat baked goods bursting with summer fruit. I think she relaxed, for once.

I notice that I’m now so protective of her. Sometimes she’s happy to let me lead, childlike, wandering around a new city. Other times, she's mad if I try to help with the frustrating laces on her winter boots.

Within these small acts of reparenting, I found myself wishing that she had been more of that safety and guidance for me as a child – but it’s not lost on me that both her parents passed away in her late twenties, just a few years apart. How quickly that must have propelled her, the eldest daughter, into a great deal of responsibility, independence, loneliness.

She didn’t really get to experience enough of this safety either. No one held her hand, but today I get to and that makes all the difference.

In the fall of 2019, I left a lover and his chaos for Montreal.

It was easy enough. Montreal is where you end up when you don’t know what to do next. It’s not a city that comforts you, fixes your problems (or its potholes), but rather one that says – merde. What can you do about it except waste an afternoon in Parc Jeanne Mance over a bottle of natural wine, surrounded by friends and beautiful strangers? Life goes on.

My mom isn’t terribly affectionate either – she won’t squeeze my hand but she’ll start the kettle, pour the tea, sigh deeply for me.

In the summer of 1986, Camille left Trinidad and her greatest heartbreak for Toronto.

She got a job as a dishwasher (short-lived), in retail at Thrifty’s (formerly Bluenotes), and as an au pair for a couple of white kids. If I close my eyes I can picture it her brief 80s anecdotes layered on top of the numerous Toronto girls’ trips I’ve orchestrated. Mama, 26, too shy to pull the cord on the bus. Making veal parmesan for someone else’s kids. Her car breaking down in a Queen Street intersection (wait, that was me).

Today I find myself gritting my teeth and being brave like my mom was (is) – getting lost in big cities, walking into rooms that don’t make way for me, leaving careless men behind, experiencing the world voraciously. I used to romanticize running away from anything that threatened to cage me, but now I realize I’m not afraid to run towards – better, brighter, newer.

Camille lives vicariously through the Whatsapp photos I send her. Did I pity her once, I wonder, for settling? How could I, when she paved the way for my freedom?

I’m standing in my kitchen in November 2022, overcommitted and burnt out, staring into space. Somewhere in my mind I believe the only way I can really heal my inner child is by returning to Trinidad to make 14-year-old Chelsea feel safe. I can’t picture what that trip would look like.

A timely Whatsapp message from my mom interrupts my melancholy – or maybe she whispered it across the country. “Eat something.” I find my way back.

All the running, the yearning to be enveloped in somewhere else, the unsettling in my bones–through it all, home is not so much a place as it is the ways I can care for myself (and thus, for others), the way I learned from her.

So I make myself some toast and tea with a dash of Angostura bitters. I read a book in bed, I call my mom while I still can–it’s early in Calgary, but she’ll be up. I tell her all my trivial life developments and I can hear her smile through her sighs.