BORN TO BE WHITE

“I swallowed American culture before I learned how to chew it.”

- Jose Antonio Vargas, Dear America: Notes of an Undocumented Citizen (2018)

Essay by Nikki Celis

Over the fall of ‘23, I bought a barong.

Not a traditional one, more modern. Embroidered in the front were two golden roosters duking it out—an homage to our love for cockfighting, or sabong in Tagalog.

Having waited a week in Calgary for the package to arrive, I felt particularly inspired by my purchase. The barong was called the Bruno—likely named after Bruno Mars. It had a boxy silhouette and—just like Bruno Mars—felt pretty culturally ambiguous if you didn’t know much about Filipino tradition and history. To be fair, most of us don’t either.

On the brand Kampeon’s website, the Bruno was created as a “testament to the Filipino spirit…[and] unyielding resolve in the face of challenges…and [our] storied past.”¹ And, while I wasn’t really feeling the name, I wanted to wear something that blended our cultural ferocity and fighting spirit with an aesthetic steeze that made me feel fierce.

As most of my days are spent in Montreal, now that I’m in my early 30s, I’ve made it a point to visit family in Calgary. I’ve started to learn Central Bikol²—mostly because I find Tagalog and the supremacy of its culture boring³—as a way to get closer to my heritage and my mother.

September 2023 was a rare occasion. This was one of the first times all first-generation cousins, including myself, would be in Calgary. To catch up, we had decided for lunch at a local Vietnamese spot, and, as I can’t drive, one of the cousins offered to give me a ride.

The Bruno had arrived from San Diego County in Southern California—the mecca of Filipino-American culture⁴—a few days before. I was excited to wear my pride. I remember feeling fierce.

Waiting outside my mom’s townhouse, my cousin pulled up in his ‘90s sedan blasting D-beat.⁵ Pounding rhythms and distorted guitars wailed as I made my way to the passenger door. My cousin couldn’t help but stare.

Before I could sit down, my cousin asked:

“What the fuck are you wearing? Some Filipino shit?”

“Yeah, man. It’s a barong.”

“Oh,” he scoffed and looked away.

Caught off-guard, I laughed. This was a familiar feeling, one that I got used to over the years. But after spending some time with Filipino, Filipina, and Filipinx artists on similar journeys of rediscovering and rewriting the scripts of our flawed hybridity,⁶ it had been a while since I had come face-to-face with cultural shame.

From language and music to food and clothes, anything considered even remotely “Filipino” was an embarrassment. Even the Bruno—essentially just an embroidered shirt if you didn’t know anything about it—was a no-no. With family, social gatherings would always center around the paleness of our skin, how American we sounded, and the appropriate people we could date.

I remember introducing an Ilocano ex-girlfriend to my extended family. She was short. Pretty. She had almond eyes with irises lighter than my mochaccino browns. She was proud yet polite. Even still, they treated her with suspicion and disdain simply for being darker-skinned and Filipina.

But hey, they didn’t hate all the Asians! Sushi, tempura, Korean barbecue, and K-dramas were all the rage. There’s a certain excitement that you could hear when they say “annyeonghaseyo” in comparison to “kumusta.” Rich Asians—white Asians⁷—were all right in our books.

This sort of shame—hiya—isn’t a stranger to my extended family, nor is it a stranger to many Filipino-Canadian/American families within the diaspora.⁸ Even within the broader context, other Asian communities have experienced various degrees of cultural shame. But what makes our collective hiya so pronounced is the way it was drilled into us. We were born to be white.⁹

With more than 381 years of Spanish and American colonialism¹⁰—over 400 years if we include America’s imperial influence—we’ve been groomed to aspire for whiteness. It’s intrinsic to the Filipino-Canadian/American common sense¹¹ and reinforced by our cultural institutions. In a 1997 essay, Allan Bergano and Barbara L. Bergano-Kinney highlight our aspirations to uphold white supremacy through interviews.

In one interview, a Filipino-American woman responds:

“[W]hite skin is considered better… Marrying a white man for Filipinas is a step up ... socially and economically…This mentality isn't new. Many of the elders here believe "White is right." All white boyfriends, husbands, and mixed children are shown off here as trophies…and not always at the doing of the girlfriend/wife.”¹²

It was common among some of my aunts and uncles to talk about how the Blacks were lazy¹³ and how the Natives were exploiting us hard-working Filipinos by taking our tax money.¹⁴ At another cousin's place in the Summer of 2022, I remember watching an episode of Atlanta, where Black reparations became a reality.¹⁵

My uncle, after watching the episode, laughed and questioned why the Blacks deserved reparations when we—Filipinos—worked and sacrificed just as much. To him, slavery was simply a notion or an elaborately conflated mythology.¹⁶

“How do you know the Africans came as slaves?” I remembered him asking me. “Maybe some of them came here for a better life.”

A part of me can understand where he’s coming from. Filipinos, too, have suffered in search of a better life. And with that dream, we’ve been used and abused for centuries under oppressive white systems that placed us in human zoos,¹⁷ exhibited as savage princes¹⁸, educated in residential school systems similar to our First Nations peoples¹⁹, and forced to till American fields and farms and orchards for hours on end with little to no pay.²⁰ But it’s also a type of minimization that comes from our desire for whiteness.

That same desire places us in a unique limbo we continuously experience when shaping and expressing our collective identity.

“It’s a limbo that alienates us from other marginalized communities, including the diasporas we’re a part of”

It’s a limbo that alienates us from other marginalized communities, including the diasporas we’re a part of. In Suspended Apocalypse: White Supremacy, Genocide, and the Filipino Condition (2010), Filipino-American abolitionist scholar Dylan Rodriguez explains that our identity is shaped as a “project of allegiance” to a settler colonial state that has used various ways to methodically control and assimilate us.²¹

This allegiance can be seen within historical systems that shape our common sense or mainstream mentality.²² It can be seen in newspapers that define what a good Filipino is (one that contributes positively as a civic citizen) and what a good Filipino isn’t (one that strays away from model attitudes and aspirations).²³ It can also be seen in institutions that reinforce our migration patterns.²⁴

In a video podcast interview with THIS IS REVOLUTION, Rodriguez says:

“…[L]ook up any Philippine consulate. They're all over the globe, obviously.

Almost everyone has a tab called 'About the Philippines.' Find how many of them mention or even imply that the Philippines was a U.S. colony. The DC consulate was the only one that explicitly said anything.

However, listen to how it was phrased…"In 1898, the Philippines became the first and only colony of the United States…Following the Philippine-American War...[t]he United States brought widespread education to the islands."

[It’s] articulated by a certain class, stratum, and certainly by a Philippine kind of state narrative as what has, in kind of absurd terms, been named benevolent colonialism.

Which is a mind-numbing contradiction…but one which I think the Philippine national narrative celebrates and valorizes in ways that become common sense.”²⁵

This, of course, isn’t the fault of the average Filipino. But it does highlight that we inadvertently reinforce a type of deliberate forgetting. It’s a forgetting that distances us from our proximity to “blackness” and “the jungle.”²⁶

“It’s a forgetting that distances us from our proximity to “blackness” and “the jungle.”’

After all, not many even know about the Filipino-American war, more appropriately labeled “conquest,” nor do we recognize that it was one of the first ethnic and cultural genocides of the 20th century.²⁷ The cultural amnesia we experience—and unconsciously enforce²⁸—helps push our continued violence into “silence and invisibility.”²⁹ This, in turn, forms the makeup of a good Filipino.

Would we find solidarity with the Blacks, the First Nations, and the Palestinians if we did remember? Maybe, if only even slightly.

Around the same time I was in Calgary, Harvey Nichol was preparing for a group exhibition for the city’s Philippine Consulate General (PCG). Set to be displayed in PCG’s José Rizal Hall, the exhibition “Malaya?”³⁰ was conceived to showcase Calgary’s diverse Filipino artists, though, oddly enough, all expenses were to be paid by the artists themselves.

Seeing as everything—from art supplies to marketing materials—was to be paid out of pocket by the artists, Nichol felt that they had room for some creative liberties. What he presented to the PCG was a radical, modern interpretation of Juan Luna’s iconic 1884 painting “Spoliarium,”³¹ depicting the ongoing state violence caused by the Duterte Administration. Victims of the drug war were suffocated with duct tape as they were dragged by penitentsya,³² cheered on by the wicked approval of onlookers or institutional bystanders.

The PCG rejected most of the pieces—created exclusively for the exhibition—until only one remained. On a call with Nichol, he explained that part of him understood why:

Nichol: During the time [this was happening], nobody would voice their concerns because, obviously, it's the consulate. If there's a place where any Filipino would want to garner respect, it would be the consulate.

Celis: Why do you think they rejected your pieces?

Nichol: These were victims of the Duterte drug war.³³ The way they would duct tape their head until they would suffocate. They would leave them in the streets with a sign saying I'm a pusher or addict. It was used as a form of vigilante justice.

I can see why [the PCG] would reject it, but I [couldn’t care less].

Celis: From your point of view, is there a reason why the diaspora tries to avoid confronting our ongoing violence?

Nichol: I think it’s because of cordial politics—[magiliw].³⁴ Not only are we encouraged to be a model minority, but as people who won't say shit. It’s properness. Pleasantry. [Being] a good Filipino.

+++

This pursuit of being as stereotypically white as can be can border on religiosity. And, in many ways, it is. The West, to us, is a place of “redemption and existential progress.”⁴⁰ It’s a place where we find ourselves closest to God, white Jesus, and the benevolent colonizers who gave us independence from Spain while shoving Elvis and SPAM down our throats⁴¹—all the while calling us “yellow n——”⁴² and “gooks”⁴³ behind our backs and “little brown brothers”⁴⁴ to our faces.

And this, for some reason, is fine because we’re good Filipinos, and if we work really, really hard, they’ll give us a pat on the back. Maybe this displacement is self-imposed. Maybe this is my shame.

Leaving Calgary was a way for me to leave my history behind. But it’s hard to shake off your experiences in the diaspora when they’re colored by shame and prejudice. Shame for being poor and uneducated. Judged for being Filipino in all the wrong ways and socialized by Alberta rednecks. Is that not a part of living as a colonized person? And if that’s the case, how do we fight to take back our pride—even if it’s just scraps?

I can think of two things: two flawed ways that we found kapwa, shared belonging, in the face of adversity. In the ring and on the stage, under the eyes of millions of White, Brown, and Black men and women, our struggles take on gendered nuances.

In the world of boxing, generations of Filipino men channel raw rebellion.⁴⁵ A-jab-to-a-feint-to-crackling-check-hook sends opponents sprawling. Their fists testify against the emasculation they face as “little” Filipino men. In this fight for respect, Filipinos have turned these events into institutions of belongingness⁴⁶ as they watched these bouts through tube TVs and now live streams and replays. It’s just like sabong.⁴⁷ These men send the Whites to the ropes, but also the Blacks and the Mexicans, too. It’s a flawed sense of resistance as we vie for a better spot in the hegemony under the auspices of the white gaze.

For Filipinas and Filipinx people, pageantry becomes a complex arena that takes up a similar stage.⁴⁸ Like dancing in a boxing ring, aspiring beauty queens compete in a dance of assimilation to the cheers of people in the crowd and at home. But, just like boxing, pageantry shares its roots in historical rebellion—roots that take shape in beauty and poise used as tools for empowerment and better status in a world of white supremacist misogyny.

These forms of resistance—as flawed as they might be—are ones that are unapologetically ours. They weren’t meant to decolonize us or make us less white. They were a way for us to feel a little less unseen. And, in a way, that’s where we found our pride, whether you agreed with it or not.

I’m not a good Filipino. Not by any means.

I grew up moving from home to home across the Calgary Northeast and spent most of my youth hanging out with blue-collar white boys. I never graduated high school, and I suffer from a deep depression³⁵ that I’ve only now been able to manage. I’m a product of an illegitimate marriage and the third son of a lineage of brothers I’ve never met: Nikon, Nikko, and me, Nikki. All I know about Nikon is that he was named after a Japanese camera company and that I was named after a Jaguar racer who burned his face off. I didn’t have the privileges to become what the diasporic common sense would call a good, upstanding Filipino. And most of all, I hate pleasantries.

Lately, the idea of belonging—kapwa at its most literal—has become a trend among community leaders, collectives, and social media influencers.³⁶ Kapwa, alongside other concepts like loób (loosely translated as one’s relational will, or how a person’s inner self is shaped by their interpersonal connections),³⁷ belongs to a growing interest in the virtue ethics of Sikolohiyang Pilipino, or Filipino Psychology.

While it can be a fantastic foundation to rediscover a flawed sense of indigeneity³⁸—and a great marketing tactic—kapwa as a surface-level concept can sometimes reinforce negative cultural values and alienate people who don’t necessarily fit the criteria of proper Filipino-ness.³⁹ Of course, some micro-communities have posited kapwa as a more nuanced trait of Filipino identity that encourages deep reflection on community healing as colonized people. But, at its roots, it’s a shared identity that manifests in ways we choose—or choose not to—inhabit.

And with that choice, I often find myself caught in this displacement. Maybe it’s because I’m jealous?

I know that I was jealous of other Filipino families and gatherings. Maybe they were as ashamed of being Filipino as we were, but during those moments when everyone in the community got together to be sosyál, that shame wasn’t there. Maybe they were just good at hiding it.

Holiday dinners with the extended family in affluent suburbia felt more like an imitation of white familiarity. Lasagna? Check. Mashed potatoes? Check. Casserole? You got it. What about something Filipino? There’s some lumpia and sweet spaghetti on the side. But hey, check out this carrot cake. The kitchen and dining table had chili and ham and everything you could find on a Food Network American dinner program, but foods that represented us—not just as Filipinos but ethnic Bicolanos—were reduced to the essentials.

“Would we find solidarity [...] if we did remember? Maybe, if only even slightly.”

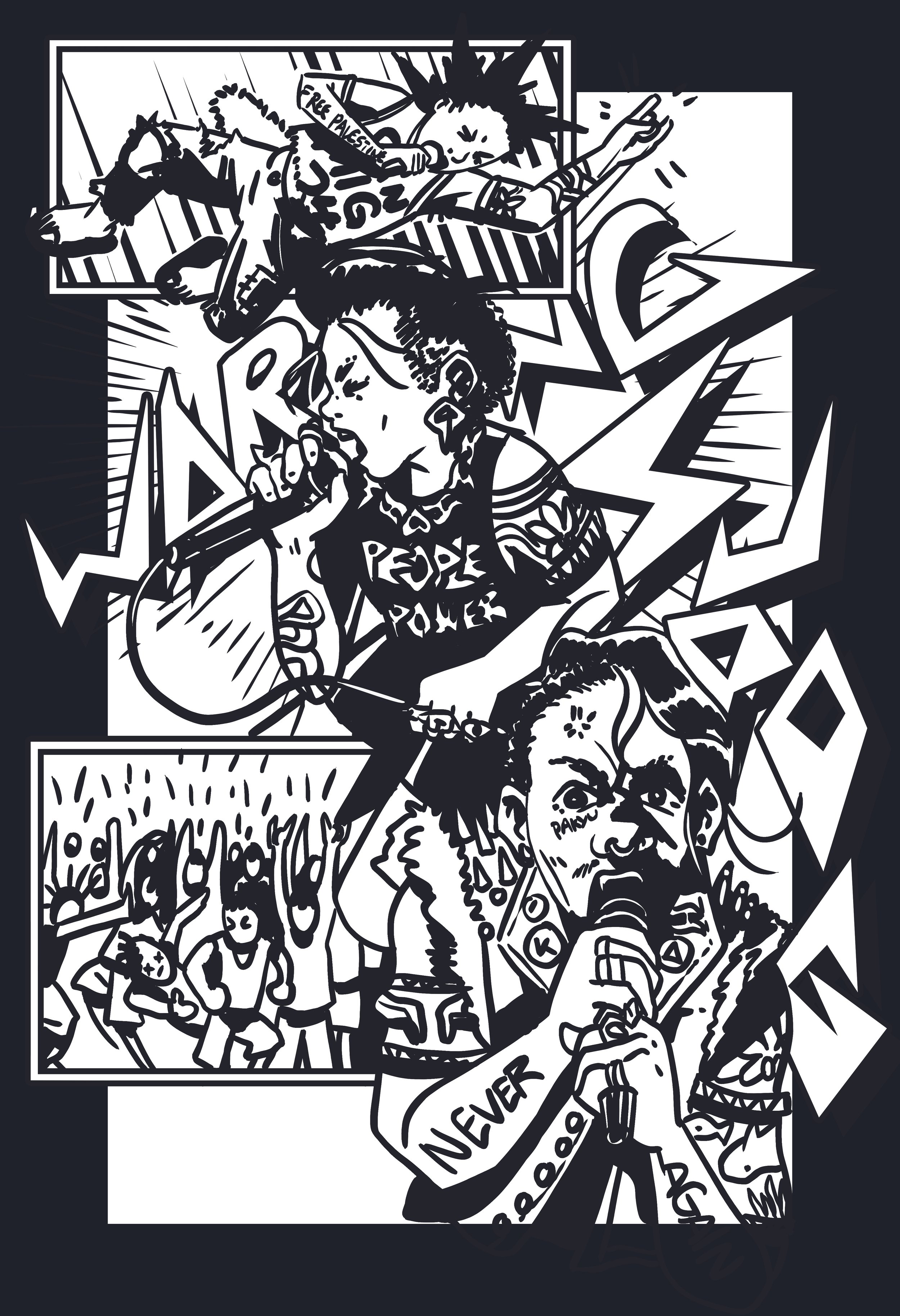

And, while I don’t consider myself a good Filipino, I can say I’m a Bicolano through and through. We’re born angry. Loud. Rebellious. It’s a tenaciousness shaped by tsunamis and volcanic eruptions and martial law. Shaped by the Whites who taught us to hate ourselves⁴⁹ and forget our languages and shaped by the Japanese who bombed our cities and libraries and skewered our babies on their bayonets as we marched to our deaths.⁵⁰ And maybe because I grew up flinging OSB into firepits and listening to Bad Brains⁵¹ while strolling through barangays, I find community (my kapwa) in punk and hardcore⁵²—just like my cousin. I hate pleasantries. I like being angry.

“Punk is, for the most part, a music of anger…a music…of chaos, even controlled chaos,” said Filipino activist, punk, and Aklasan Records founder Rupert Estanislao in a documentary interview with The Sago Show.⁵³

“Most Filipinos don’t get into it, but there are Filipinos that don’t feel the same way as everybody else. They have issues, and they have anger, and they’ve suffered through something, and they want to express that suffering…their experience. So, they find it through [punk].”⁵⁴

As Filipinos, we find our pride through imagined fantasies of the motherland and express it lovingly through writing and music and visual art—but where are the outliers that talk about our pain? Anti-colonialist thinker Benedict Anderson observes the lack of expressions rooted in anger among the colonized—a reflection of our pride and aspirations to be a good Filipino. “It is astonishing,” he writes, “how insignificant the element of hatred is in these expressions of national feeling.”⁵⁵

If there’s anything you should know about Bicolanos, it’s that we know how to get mad. We’re feisty like that. Define us by a set of generalisms and one of those traits would be orag,⁵⁶ “the oomph that makes a person oragon”⁵⁷—someone determined, unafraid of the consequences. With all its language variations and regional dialects, Bikol is the only language family in the Philippines with its own “angry register,” a set of expressions also called rapsak. And if that isn’t punk, I don’t know what is.

In the diaspora and the motherland, you’ll find punk and hardcore shows in basements and dive bars. In empty churches and subway tunnels and busy underpasses. Distorted guitars and pounding rhythms blast through worn-out speakers while the frontman gives a lucky person the microphone and the chance to yell, scream, and shout. Kapwa can be found here, too, even if it belongs to people who choose to live dismantled and broken. Here, you feel less invisible and without shame.

Walang hiya. Warang supog.

To accompany this text, Nikki Celis has curated the playlist: “BIPOC Skramz, Punk, and Hardcore.

¹ “About The Bruno 1.0 – KAMPEON CO,” accessed December 15, 2023, https://kampeon.co/pages/about-the-bruno.

² Bikol is one of the major languages of the Philippines, spoken in various sub-languages and dialects by ethnic Bicolanos.

³ J.J. Smolicz, “National Language Policy in the Philippines: A Comparative Study of the Education Status of ‘Colonial’ and Indigenous Languages with Special Reference to Minority Tongues,” Southeast Asian Journal of Social Science 12, no. 2 (1984): 51–67.

⁴ Jeanne Batalova Caitlin Davis and Jeanne Batalova, “Filipino Immigrants in the United States,” migrationpolicy.org, August 7, 2023, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/filipino-immigrants-united-states. With almost 2 million Filipinos in the United States alone, Filipinos represent one of the largest minority groups in the country, with 48 percent of them living in California.

⁵ A sub-genre of hardcore punk, named after the 80s hardcore group Discharge.

⁶ Dylan Rodriguez, Suspended Apocalypse: White Supremacy, Genocide, and the Filipino Condition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 45. Rodriguez criticizes certain approaches to forming the Filipino-American identity that simplifies and minimizes the individual violence that many Filipinos in the diaspora face by linking them to generalized cultural and psychological issues.

⁷ A reference to the issues of representation in the Asian diaspora. See: J. Maraan, “Understanding the Asian American Divide,” April Magazine, August 2, 2018, https://www.aprilmag.com/2018/08/02/understanding-the-asian-american-divide/.

⁸ Martin F. Manalansan IV, “Unpacking Hiya: (Trans)national “Traits” and the (Un)making of Filipinxness” in Filipinx American Studies: Reckoning, Reclamation, Transformation, eds. Rick Bonus and Antonio T. Tiongson (New York: Fordham University Press, 2022), 374-376.

⁹ Not in the literal sense. The phrase illustrates how aspirations for whiteness get passed down through generations. Aspiring for whiteness is a cultural trait nurtured from birth.

¹⁰ Spain colonized the Philippines for 333 years until being liberated by America in 1898. From then to 1946, America would leave a lasting colonial influence in the Philippines, shaping our colonial mentality today.

¹¹ Rodriguez, Suspended Apocalypse, 4. Referencing Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci, “common sense” can be understood as a shared way of seeing the world. This common sense is influenced by various social, cultural, and political factors that are used by the dominant culture to shape the common sense in their interests. For Filipinos in the diaspora, this would be used in many ways to reinforce white supremacist values.

¹² Allan L. Bergano and Barbara L. Bergano-Kinney, “Image, Roles, and Expectations of Filipino Americans by Filipino Americans” in Filipino Americans: Transformation and Identity (Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., 1997), 202.

¹³ A common stereotype of the Black Canadian diaspora that reinforces white supremacist values.

¹⁴ A common stereotype and misconception among conservative-leaning Canadians and Filipino-Canadians.

¹⁵ "The Big Payback," season 3, episode 3, Atlanta, directed by Hiro Murai, written by Francesca Sloane, aired on FX, March 24, 2022.

¹⁶ “Mythologies” can mean the common beliefs and ideas that society accepts as true without questioning. These can include oversimplified (and often stereotyped) ideas about different races and cultures. For example, the belief that a group of people act a certain way can become a “myth” that many accept as fact, even if it isn’t true. This can be seen in how media, like TV shows or news reports, often repeat the same kinds of stories about certain groups, reinforcing these myths. For a study on how mythologies influence modern culture, see: Roland Barthes, Mythologies (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1957).

¹⁷ “Tribal Headhunters on Coney Island? Author Revisits Disturbing American Tale,” Adventure, October 28, 2014, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/article/141027-human-zoo-book-philippines-headhunters-coney-island.

¹⁸ LIO MANGUBAT | Nov 2 and 2017, “The True Story of the Mindanaoan Slave Whose Skin Was Displayed at Oxford,” Esquiremag.ph, accessed December 16, 2023, https://www.esquiremag.ph/long-reads/features/the-true-story-of-the-mindanaoan-slave-whose-skin-was-displayed-at-oxford-a00029-20171102-lfrm2.

¹⁹ Anne Paulet, “To Change the World: The Use of American Indian Education in the Philippines,” History of Education Quarterly 47, no. 2 (2007): 173–202.

²⁰ “Remembering the Manongs and Story of the Filipino Farm Worker Movement,” National Parks Conservation Association, accessed December 16, 2023, https://www.npca.org/articles/1555-remembering-the-manongs-and-story-of-the-filipino-farm-worker-movement.

²¹ Rodriguez, Suspended Apocalypse, 29.

²² Rodriguez, 4.

²³ Rodriguez, 54. Rodriguez uses the newspaper Philippine News Today as an authority that has shaped mainstream Filipino views since its inception in 1961.

²⁴ Such as the Philippine Consulate General or the employment prospects reinforced by American Imperialism (nursing and military service).

²⁵ Philippines Independence Day (Ft. Dylan Rodriguez), 2023, 53:18 to 54:13 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fyKxw7p4DkI.

²⁶ Rodriguez, Suspended Apocalypse, 142.

²⁷ “Why the Story of the United States Needs to Be Challenged,” Berkeley, 2022, https://news.berkeley.edu/2022/04/12/why-the-story-of-the-united-states-needs-to-be-challenged. Pre-dating the Armenian genocide (1915-1923), the Filipino-American War (1899-1902) resulted in the deaths of roughly 200,000 Filipinos. Some, however, contest that the casualties tolled up to the millions.

²⁸ Rodriguez, 34. The construction of the Filipino-American identity is one that contributes positively to American society as a civic citizen. In turn, Filipinos act in a way that may reinforce white supremacist institutions and cultural values.

²⁹ Rodriguez, 140.

³⁰ Tagalog for “freedom.”

³¹ “About,” SPOLIARIUM (blog), accessed December 15, 2023, https://www.spoliarium.com/about/. One of the national symbols of the Philippines that inspired the 1896 Philippine Revolution.

³² A religious fundamentalist group in the Philippines known for self-flagellation.

³³ The Philippines' "war on drugs" led to the deaths of more than 12,000 Filipinos (some say 20,000), many through extrajudicial killings. For an in-depth look at the human impact of Duterte's drug war, see the documentary "The Nightcrawlers" on National Geographic, available at https://www.natgeotv.com/uk/shows/natgeo/the-nightcrawlers.

³⁴ Tagalog for “gentle” or “pleasant.”

³⁵ See: “How the Philippines’ Colonial Legacy Weighs on Filipino American Mental Health,” Los Angeles Times, October 13, 2021, https://www.latimes.com/lifestyle/story/2021-10-12/colonial-history-behind-filipino-american-mental-health.

³⁶ Andi T. Remoquillo, “The Problem with Kapwa,” Alon: Journal for Filipinx American and Diasporic Studies, no. 3(1) (2023): 8, https://doi.org/10.5070/LN43161818.

³⁷ Remoquillo, 8.

³⁸ Remoquillo, 11.

³⁹ Martin F Manalansan Iv, “Unpacking Hiya," 368.

⁴⁰ Rodriguez, Suspended Apocalypse, 186. Rodriguez writes, “’America,’ for the Filipino national bourgeoisie and its Filipino American derivatives across “class” strata, is a site of redemption and existential progress, an imagined journey that invokes the Catholic ritual of Confirmation, wherein the adolescent subject undergoes an ornamental training in the responsibilities of the adult Christian.”

⁴¹ Doreen G. Fernandez, “Mass Culture and Cultural Policy: The Philippine Experience,” Philippine Studies 37, no. 4 (1989): 490–93.

⁴² The term was used as a way to associate us with our proximity to blackness and the jungle—particularly for those who resisted the American occupation. See: “Natividad: The Names They Gave Us Cut Deep,” Berkeley, 2022, https://news.berkeley.edu/2020/11/19/natividad-the-names-they-gave-us-cut-deep.

⁴³ David R. Roediger, "Gook: The Short History of an Americanism," in Towards the Abolition of Whiteness: Essays on Race, Politics, and Working Class History, Reprinted, The Haymarket Series (London New York: Verso, 2000), 117–119. Used to reference Filipinos and their raciality, particularly the absence of European, civilized blood. Roediger posits that its origins may date back earlier than 1935.

⁴⁴ See: Gideon Lasco, “‘Little Brown Brothers’: Height and the Philippine–American Colonial Encounter (1898–1946),” Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints 66, no. 3 (2018): 375–406, https://doi.org/10.1353/phs.2018.0029.

⁴⁵ Bernard James Remollino, “Scrapping Into A Knot: Pinoy Boxers, Transpacific Fans, and the Troubling of Interwar California’s Racial Regimes,” Alon: Journal for Filipinx American and Diasporic Studies 1, no. 2 (2021): 179.

⁴⁶ Remollino, 151.

⁴⁷Cockfighting

⁴⁸ See: Genevieve Alva Clutario, Beauty Regimes: A History of Power and Modern Empire in the Philippines, 1898-1941 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2023).

⁴⁹ See: “Filipinos, Colonial Mentality, and Mental Health | Psychology Today Canada,” accessed December 15, 2023, https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/unseen-and-unheard/201711/filipinos-colonial-mentality-and-mental-health.

⁵⁰ Joan Orendain, “February 1945: The Rape of Manila,” INQUIRER.net, February 16, 2014, https://globalnation.inquirer.net/99054/february-1945-the-rape-of-manila. Orendain writes, “Unborn babies ripped from their mothers’ wombs provided sport: thrown up in the air and caught, impaled on bayonet tips.”

⁵¹ Seminal 80s African-American hardcore band.

⁵² I say “kapwa” here as my own flawed sense of shared identity. Punk is largely a white-dominated genre. Just like boxing and pageantry, the marginalized navigate these spaces in search of community as outliers with an anger they want to express.

⁵³ Filipino Punks & Vegan Adobo: Lasa and Legacy, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nentz97Bw78.

⁵⁴ Filipino Punks & Vegan Adobo, 2:37 to 3:12.

⁵⁵ Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1991), 142

⁵⁶ Bikol slang. Loosely translated as “tough” or “toughness.”

⁵⁷ Ma Ceres P. Doyo, “‘Oragon,’” INQUIRER.net, November 12, 2020, https://opinion.inquirer.net/135221/oragon.